Chapter 1

A Musical Vocabulary

What is music? You have most likely asked yourself this question many times. As you become more serious about the study of music and developing your musicianship, you will probably find yourself asking this question more and more. Asking this question is similar to asking, "Who/what/how is God?" There is no definitive answer. Instead the answer is too subjective – the definition of music is different for everyone. However, a good start is to define music as "sound organized by humans." Obviously, this is also an argumentative statement in and of itself, but it can serve as a springboard for us as we discuss why we study music.In high school, I once questioned a math teacher why it was important for me to solve some algebraic equation. The answer she gave surprised me, and today I think it is relevant to our discussion of why we study traditional music. The teacher simply told me that it was important for me to be able to solve the math problem because other people had solved it, and if they thought it was important enough to solve, I should at least investigate it. Of course this was a great way to get an annoying student like me to be quiet, but I still find meaning in her answer. With a little creativity, I later realized that she was echoing the statement of a famous 20th century composer, Hans Werne Henze, who to paraphrase said that we are only the sum of what has come before us. In music, we canʼt become better listeners unless we have at least a cursory understanding of music and a musical vocabulary.

Notation Background

The primary role of musical notation is to effectively and efficiently communicate music ideas to performers, but there are many examples of notation that also are visually artistic. The music above was written by early American composers, William Billings (1746-1800), who had a unique sense of humor. This song is intended to be sung as a "canon" which is more commonly known as a "round." This song begins at the top with the word, "Wake" and processes in a clockwise direction. Once the first sentence is completed, the second voice begins on "Wake" and so forth until all voices have entered.The most famous round of all times is Row, Row, Row Your Boat.

Listen to the women of the Lewis University Choir sing Billings' Wake Ev'ry Breath below. In this version, the choir sings the entire melody together first in unison which simply means that every part is singing the same pitch at the same time.

Notation is simply a guidebook for performers. It is actually very imprecise, and can be interpreted many different ways. How boring music would be if notation were extremely precise! How interesting is hearing Beethoven's 9th Symphony exactly the same every time? Obviously, it would become monotonous, and it probably would not have survived as one of the greatest works of all time.

The three basic building blocks of music are rhythm,

With technology today, it is possible for composers to specify exactly how an event should be played. Composers can define the amplitude,

Systems for writing down music has been around since the ancient Greek civilization. During the middle ages, the dawn of Gregorian chant, music was hand written on big table size sheets of paper. These sheets had to be big enough for the entire choir to see simply because it was too costly to produce several copies of the same music (Medieval Powerpoint maybe?). Churches and royal courts had their own unique collections of music. During this time, if you lived in France you would most likely not know the music from a church in Italy. Simply it was too costly to mass-produce music for distribution. Notated music was so cherished that manuscripts were often copied out by hand and given as expensive gifts. It wasnʼt until the 15th century when Johan Gutenberg printed the Gutenberg bible, the first printed book produced using movable types, did music notation really start flourish. Printed in 1473, this work not only contained biblical scripture, but also included Gregorian chant. With his invention, people, institutions, and churches were finally able to share music. The first collection of printed polyphonic music, or music with more than one voice, is attributed to Ottaviano deʼ Petrucci in a 1501 publication. Petrucci published 59 volumes using movable type by 1523! As you can see, the invention of movable type was a mechanism that helped distribute, and more importantly, standardize music notation.

Learning to read music notation is beyond the scope of this text, but it is something that can make listening to music more enjoyable. There are numerous websites that you can visit to learn how to read music. Music notation, as well as music itself, is very similar to language. It takes practice to become fluent in a language, and music is no different.

Basic Acoustics

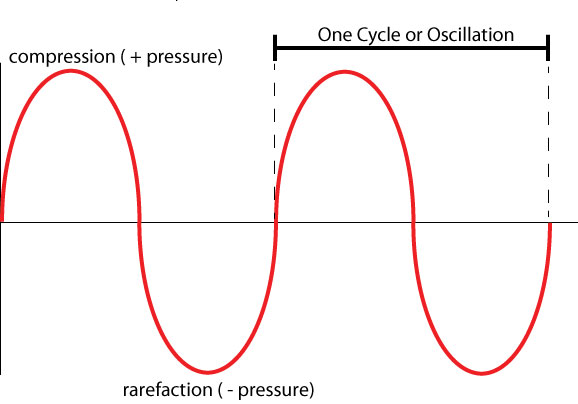

What is sound? At first glance, this question may seem pretty simple but upon further inspection, I think you will find that many of us take sound for granted. You might remember from high school science classes something about sound having to do with waves with crests and troughs. You probably learned at some point about transverse and longitudinal waves. For our purposes, we just need to understand that sound is the compression (squeezing) and rarefaction (expanding) of a medium's pressure. The medium is usually air, but sound travels through a number of mediums like water. In other words, sound is a pressure wave and when an object vibrates it creates a disturbance, or change in pressure, in the medium.When a string vibrates for example, it excites the air molecules nearby and compresses and rarefacts these molecules, thus changing the air pressure. Thinking back to your high school science class, the "crest" of the wave is the compression of the air molecules while the "trough" is the rarefaction of the air molecules. One compression and rarefaction of air molecules is called an oscillation or cycle. How quickly an oscillation occurs is called the frequency and is measured in cycles per second (cps) or hertz (hz).

Figure 1 - Simple Sine Wave

This graphic represents a model of a sound wave. The x-axis is time and the y-axis is pressure. As the pressure increases the air molecules compress. How often a compression/rarefaction occurs within a second determines the frequency of the sound. The amount or power of compression and rarefaction determines the amplitude of the sound.

A sine wave is often used by teachers and textbooks to represent sound; however, a pure sine wave is theoretical and does not exist in nature. Named after the French mathematician, Joseph Fourier, Fourier's law states that any sound wave could be modeled combining multiple sine waves. This basic principle has had a profound impact on music and science.

Pitch

Pitch is a musical term of how we perceive frequency. If the frequency is higher, then we will perceive the pitch to be higher. Likewise, if the frequency is lower, or there are few cycles of the sound wave per second, then we will perceive the pitch as being lower. Humans can hear frequencies from approximately 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz (20khz). Fortunately in music, we don't play music by interpreting frequencies, however. Music is much more simple. In the Western world, we use a series of dots and lines (music notation) to tell performers what pitch to play on their instrument.Just like most other languages, music has its own distinct alphabet. Luckily, this musical alphabet is part of our English alphabet. Our basic musical alphabet contains only seven letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, G. In written music, notes are placed on a staff and depending on the clef, we label each note with one of these letters. To help communicate pitch orally, we have assigned letter names to specific pitches, but those pitches align with specific frequencies. For example, the pitch "A" that can be found near the middle of the piano keyboard is often referred to as "A 440" because that pitch ("A") has a frequency of 440 hz, or 440 cycles per second. 440Hz, in our Western musical system, happens to be the "A" above middle C, and is the pitch orchestras in the United States use to tune – it is also known as "concert A". In Europe, their concert A is 441Hz. The difference between 440Hz and 441Hz is not recognizable to the normal ear unless you listen to the two simultaneously. I'm not sure why the Europeans use a different tuning scale, but it's an interesting trivia fact you can use to impress people at your next cocktail party.

You're probably saying to yourself, "but wait, there are more than 7 pitches in music." You are correct. In Western music we actually have 12 pitches, equally spaced, per octave. Huh oh...what is an octave? An octave is the interval, or distance between two notes, that share the same letter name and whose ratio of frequencies is 2:1. In other words, if you want to play the octave above A-440, the pitch name, or note name, is still "A", but the frequency will be doubled, or 880hz (2:1 ratio). Similarly, to play the octave below A-440, the note name would remain "A", but the frequency is 220hz.

Dynamics

Dynamics is a musical term used to describe how we perceive amplitude or volume. How loud or soft a note or passage is played can really effect the mood and emotional quality of the piece. For example, sing the first verse of Amazing Grace three times. The first time, try to sing it at a moderate level throughout without any amplitude inflections. The second time, sing the song a softly as you can throughout. Finally, sing Amazing Grace at first very soft, and gradually become louder until you reach "Was blind, but now I see." Sing this last sentence very softly. How are each of the emotional responses different for these three versions?Dynamic Markings

: pianississimo : extremely soft

: pianississimo : extremely soft

: pianissimo : very soft

: pianissimo : very soft

: piano : soft

: piano : soft

: mezzo piano : medium soft

: mezzo piano : medium soft

: mezzo forte : medium loud

: mezzo forte : medium loud

: forte : loud

: forte : loud

: fortissimo : very loud

: fortissimo : very loud

: fortississimo : extremely loud

: fortississimo : extremely loud

There are really only two main categories for dynamics: "soft" and "loud" (and you thought this course was going to be difficult). The Italian term piano (pronounced just like the instrument) indicates "soft" and forte (pronounced "Fór-teh") means loud, but these may easily also be expanded to "very loud" or "extremely soft" simply by adding additional letters to the dynamic marking. The Italian word, mezzo (pronounced "Mét-so") is also added to piano and forte to indicate "medium soft" and "medium loud."

In addition to telling the performer the amplitude of how an event is to be performed, dynamics can also tell the performer the mood of how something is to be performed because when looking at dynamics, performers must take into account the context. For example, the dynamic range for some works, like Mozart's Missa Brevis in F Major may only be from piano to forte. In other works like Tchaikovsky's 6th Symphony, the dynamic range is from pianississississississimo (6 p's) to fortississississississimo (6 f's)! This doesn't mean that the Tchaikovsky symphony will necessary be played louder or softer (although it may due to the size of the orchestra), but that Tchaikovsky really tried to be more accurate in communicating to the performer his desires. Where Mozart used only a handful of dynamic markings, Tchaikovsky used many. In other words, Tchaikovsky tries to control how his music is performed to a greater degree.

To add more interest, composers ask performers to change their dynamics over time. Again, the majority of these terms today are now written in Italian, which are provided in the figure below, but other composers wrote in their vernacular. Today, many English-speaking composers have adopted a variety of methods. Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) for example wrote paragraphs of text in his musical scores in an attempt to give as much information to the performer as necessary. Likewise, many composers today like composer Brian Ferneyhough, also include numerous performance indications in musical scores. These include not only dynamics, but also sentences about balance and what a performer should listen for in the other parts. Not surprisingly, Ferneyhough has been very successful in receiving oustanding performances of his music.

Timbre

Regardless of pitch or volume, musical sounds have one other important difference: tone color. The tone color, or timbre (pronounced "tám-br") is probably the most difficult musical characteristic to understand, but is probably the most recognizable and intuitive as a listener. For example, if are you able to tell the difference between a flute and a saxophone? If you can, then you are able to recognize two distinct timbres! Now imagine if you were asked to tell the difference between the pitch "C" and the pitch "F". Being presented with these two pitches outside of a musical context, you most likely would be able to tell whether the first note was higher or lower than the second, but unless you have perfect pitchAt its genesis, timbre is determined by a combination of frequency, amplitude, time, and space. As mentioned before, Fourier's law states that any sound wave could be modeled combining multiple sine waves. How these many sound waves interact with one another determines how we perceive the tone quality.

The science of timbre is extremely complex and certainly beyond the scope of this book; however, a basic understanding of timbre will help you develop your listening skills and provide you with a vocabulary to internalize and communicate your listening experiences. One can think of the discussion in the previous paragraph on Fourier's law as a discussion of sound at a "quantum" level. As we zoom out from this perspective, we can begin to speak about music in broader terms. One term that is often found in texts about the science of sound and is the primary cause of timbre quality is overtone.

Many try to use adjectives to describe timbre: warm, bright, dull, hollow, dark, brassy, etc.; however, these terms are too subjective and ambiguous. Oddly, the most easily recognizable characteristic in music is actually the most difficult to articulate, and this is one reason I believe that music is so remarkable and amazing.

Tempo

Tempo is the speed of the beat of a composition or a section of a composition. It can vary from very slow to very fast and can be indicated by a series of Italian terms (largo [broad], lento [slow], adagio [slow and relaxed], andante [walking pace – medium], moderato [moderate], allegretto [quick], allegro [fast], presto [very fast], vivace [fast and vivacious] and prestissimo [as fast as possible]. It also can be indicated more precisely by metronomeBecause tempo can vary greatly, the duration of any type of note value becomes highly variable. A quarter note

In archaic and early medieval European music tempo was thought to relate to a normal human heartbeat, and was conceived as a broadly fixed amount of time. From the 13th to the 15th Century these units were called tempus and were represented by certain note values that represented normal beats or units of time. In the 15th and 16th Centuries the term, tempus, was replaced by the term, tactus, and the kind of note value that represented a beat also changed. The modern use of varied tempos began to come into practice in the middle of the 17th Century.

In 19th, 20th and 21st century music composers tend to carefully indicate tempos in their pieces. Performers usually follow these indications. However, questions of interpretation as well as external factors such as the size and/or ability of a performing ensemble or the size and acoustics of a concert venue often influence modest deviations from stated tempos.

Chapter 1: Music for Listening